The Hazy History of Smoking Bans

The tobacco industry has long been a hub of controversy due to its health hazards and lack of transparency in advertising. Prior to the prosperous days of Madison Avenue spin, tobacco culture thrived amongst natives of the Western hemisphere. The plant was smoked, chewed, and insufflated for centuries before usage caught on in the Old World following Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic. An Englishman who took up smoking shortly after the explorer’s return to Europe was famously thrown in jail on suspicion of being the devil because of the “steam” escaping from his mouth and nose.

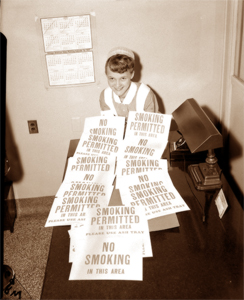

By the mid-1950s, the connection between smoking and poor health was becoming widely appreciated. At this time, US hospitals started to create both Smoking Permitted and No Smoking Areas. From the SmartSign archives: Joanne Downing, student nurse, installs new fire prevention signs at St. Luke’s Hospital, 1957. Photo from Author’s Archives.

Marshall Fields posts

new No Smoking signs at the department store in 1948.

The mystique surrounding the habit has fueled a billion dollar industry throughout Europe and North America that continues to deny the dangers of the nicotine and carcinogens present in cigarettes. Capitalizing on the supposed glamor of a habit that defies death at every drag, cigarette companies like Lucky Strike and Camel had the U.S. vice industry in a stronghold throughout much of the twentieth century. Studies in the fifties had tobacco giants scrambling to install filter-tips on their products. Beyond this publicity stunt, tobacco companies decided that addiction outweighed the surgeon general’s warnings. They continued their commercial ploys into the sixties, infiltrating children’s magazines and women’s weight concerns, spurred by the rise of Twiggy and other hyper-thin supermodels.

A Lucky Strike print

advertisement, circa 1930s.

For as long as the cigarette and tobacco industry has flexed its corporate prowess, critics have maintained their opposition. Even before scientific studies were conducted, skeptics questioned the safety of inhaling any type of smoke, especially when it was the result of burning a mysterious plant from faraway lands. One of the first published works criticizing the use of tobacco was a treatise written by King James I of England in 1604, passionately titled

A Counter blaste to Tobacco. In it, the king wrote of tobacco’s putrid smell and pondered its potential detriment to the lungs. The piece, written in Early Modern English, was one of the first anti-tobacco articles ever published.

Over the centuries, other entities have exercised bans to support criticism of tobacco. In 1833, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints published their Word of Wisdom, which banned smoking on account of it not being “…for the body, neither for the belly, and is not good for man, but is an herb for bruises and all sick cattle, to be used with judgment and skill.” (Doctrine and Covenants 89:8). When Richard Doll published his findings that linked smoking to lung cancer in the British Medical Journal in 1950, there was public outcry. Yet the advertising agencies behind widespread sensationalized campaigns for cigarette companies weren’t legally obligated to include a surgeon general’s warning on their products for another fourteen years.

Surgeon General’s Warnings were added to cigarette

advertisements and boxes in 1964.

The earliest known smoking ban was enacted in 1575, when a Mexican ecclesiastical council declared tobacco in any church in Mexico or Spanish colonies illegal. Pope Urban VII followed suit, banning smoking in the Church in 1590, threatening to excommunicate anyone found with tobacco in any form in or around a place of worship. In 1633, the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV placed a ban on smoking throughout his entire empire. The late seventeenth century found numerous European cities enacting similar prohibitions. Bavaria, Kursachsen, and a handful of regions in Austria banned smoking in government and religious buildings. One of the first individual buildings in the world to set its own smoking regulations was the Old Government Building in Wellington, New Zealand in 1876.

Modern day

No Smoking signs

like this humorous one owe their existence

to a long history of smoking bans and education.

While it’s difficult to identify exactly when the first smoking bans appeared in the U.S., some of the oldest-known No Smoking signs that exist today date back to the late 1800s. The institutions that first enacted smoking bans were gas stations, since the chemical threat of flame interacting with gasoline superseded any sociopolitical or health concerns about tobacco. Texaco, formerly named “The Texas Company,” is one of the oldest gasoline franchises in the United States. Their implementation of No Smoking signs created a precedent for fellow organizations that quickly followed suit.

An antique porcelain Texaco No Smoking sign.

In the rest of the world, smoking bans as a result of predicted health risks appeared much earlier than in the US. Nazi Germany was one of the first regimes to attempt to ban smoking in every post office, university, military hospital and government office. Karl Astel, a Nazi officer, headed the Institute for Tobacco Hazards Research. The institute was founded in 1941 under the orders of Adolf Hitler, who encouraged a number of anti-tobacco campaigns until the demise of Nazi rule in 1945. Despite the indoor smoking regulations, the Nazis still depended heavily on tobacco products while performing duties outdoors. Hitler personally denounced the habit, although he had been a heavy smoker in his earlier life, consuming upwards of thirty cigarettes each day.

Despite the ostensible health awareness behind the implementation of such a ban, the Nazis actually upheld these indoor rulings for many of the same reasons they upheld their other prejudices. They believed tobacco made women vulnerable to premature aging and loss of physical attractiveness, as well as hindering their reproductive abilities. For a society that strived toward a twisted genetic “perfection,” smoking simply presented a possible detriment to the supposedly elite and virile Aryan race.

Back across the pond, another American critique of smoking as a health risk had yet to be published for nearly another decade. The aforementioned article by

Richard Doll linking cigarettes to lung cancer initiated debate, yet it took fifty years for smoking to be widely banned in restaurants, schools, and flights. In fact, smoking was still allowed on a number of international flights through 1999. Although Doll’s findings were met with widespread concern and increased awareness, big tobacco companies worked hard to sell their products and the smoking lifestyle to American consumers. Only a few public spaces implemented bans in the fifties. Whether concerned by an increasing awareness of smoking on the health of their clientele or a devastating history of fires, by the 1950’s no smoking and smoking permitted areas were found at hospitals and department stores.

An ashtray on an older-model

international airplane.

The industry launched “courtesy awareness” campaigns to transition the public’s consternation from the dangers of first and second-hand smoke to a matter of proper smoking etiquette between smokers and non-smokers. This eased tensions for a number of years, although there was a growing subset of Americans who found the tobacco industry’s endeavors to be intentionally misleading when it came to the very real dangers of smoke exposure in public spaces. Even if smokers were polite about their habits, health concerns were increasingly widespread as the U.S. entered into the sixties – an era of questioning authority and big corporations.

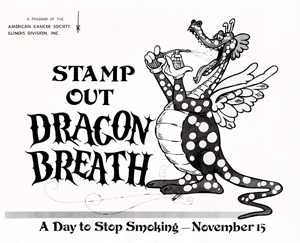

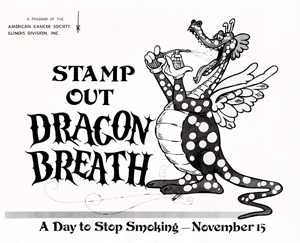

The American Cancer Society campaigned in 1979

to stop smoking, with the incentive of “putting out” bad breath.

In 1975, Minnesota was the first state to regulate smoking, introducing a ban on smoking in most public spaces. The

Minnesota Clean Indoor Air Act paved the way for other U.S. states to implement similar regulations. In 1985, the town of Aspen, Colorado became the first U.S. city to restrict smoking in restaurants. Meanwhile, a reworking of the Minnesota legislation in October 2007 extended a requirement for “No Smoking” sections in restaurants to a ban on smoking in all restaurants and bars. This iteration of the act was appropriately renamed the Freedom to Breathe Act.

Following these two seminal moves in smoking prohibition, a number of other U.S. cities began enacting their own legislation against smoking. In 1987, the city of Beverly Hills, California passed laws to ban smoking in restaurants, stores, and at public gatherings. Hotel restaurants were the only exemption to this ruling. Lawmakers argued that such establishments were more likely to cater to international guests who would be accustomed to smoking while eating at dinner.

In the 1990s, smoking bans became much more widespread throughout the United States and abroad. In 1990, San Luis Obispo, California, became

the first city in the world to adopt an indoor smoking restriction in all public places, including all bars and restaurants. The state of California banned smoking in all bars statewide four years later. In Peru, smoking in enclosed public spaces and on public transportation was banned. Six years later, India banned public smoking, citing it as a violation of the Indian Constitutional health codes, with an added concern about potential air pollution.

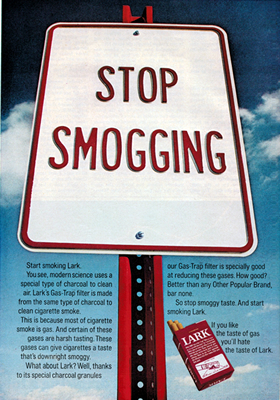

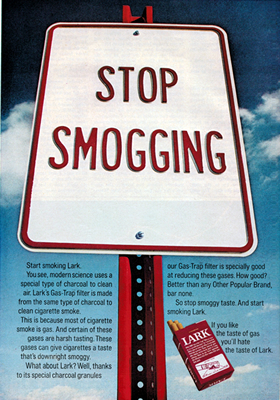

Until very recently, the idea of a

smoking ban was silly fodder for cigarette

advertisements like this Lark magazine spread.

Today, widespread public smoking continues to take a hit, with even Europe’s infamously lawless beaches banning the wheeze-worthy pastime. As of April 2012, only ten U.S. states have not yet instated general bans on non-government owned spaces. Even so, Alabama, Alaska, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, West Virginia, and Wyoming all have a handful of individual cities and counties that have implemented their own smoking bans.

The rapidity with which smoking bans have arisen in the last half-century has had a significant effect upon tobacco product sales and even on smokers themselves. Although many bans have been enacted with second-hand smoke victims in mind, the existence of such prohibitive public spaces has been shown in studies to reduce first-hand smokers’ frequency of consumption by between 11% and 15%. In addition, within eighteen months of Pueblo, Colorado’s ban on smoking in 2003,

admissions to the local hospital for heart attacks dropped by 27%. Neighboring towns that had not introduced similar bans did not experience a change, implying that the Colorado city’s cleaner air quality had a positive effect on residents’ heart and lung health. Lastly, cigarette companies have suffered with the recent rise of smoking bans, despite a core of lifelong consumers dedicated to the highly addictive habit.

It’s now commonplace for citizens in the U.S. and around the world to encounter No Smoking signs in the public spaces they frequent. Although the dissemination of knowledge regarding the dangers of smoking and using other tobacco products is a long-term process, the past several decades can give the U.S. hope for a cleaner, healthier future as a country and a planet. So step outside and take a deep breath, of clean, smoke-free air.