Civil Rights Historical Landmark Missing Twice: Once as a Prank, Once as a Repair

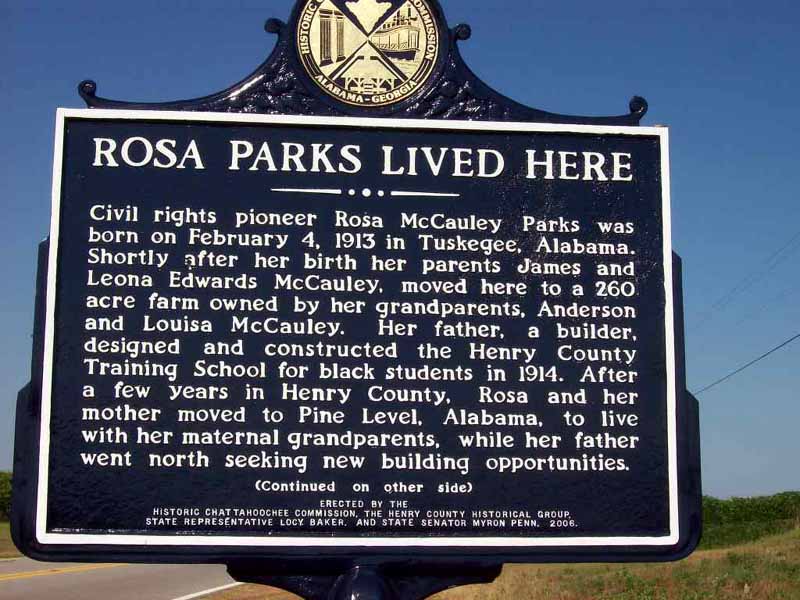

If not for the sign, would we still remember? (via USGWArchives.com)

9/17/2012 — In late August, the historical landmark denoting the childhood home of Rosa Parks was reported missing. After an article by the Dothan Eagle, the Department of Transportation came forward the next day to say they had damaged it while mowing the lawn along Alabama Highway 10 outside Abbeville.

“We’re glad to know where it was at because that was a very popular historic marker around here,” Henry County Sheriff Will Maddox said. “We’re just glad there was no criminal mischief behind it.” DOT officials apologized for the oversight of failing to alert anyone in the Sheriff’s office while they were having it repaired.

“We were getting a good many calls on it,” Maddox said. This was not the first time his office had investigated the missing sign. In 2008, the same sign was reported stolen, also on Sheriff Maddox’s watch. This time, three Ozark boys were convicted of a felony after the story broke. At the time, Maddox quantified the theft as “just mischievous,” citing the boys’ cooperation in retrieving the sign from the Dale County creek where they had dumped it.

The childhood home of Rosa Parks, located in Abbeville, Alabama. The formative years of the Mother of the Civil Rights movement remind us of our own place in American history. (Photo via Jimmy Wayne)

Residing primarily under the jurisdiction of the local or state government, a community made up of private organizations and citizens will often move and fundraise to erect a historical sign that they deem culturally significant. Governments work with private citizens to determine the best design, placement and content for such a sign. For example, the Alabama Historical Commission requires final approval of the narrative text as well as an erection ceremony of the proposed sign (but will allocate no funds toward the project).

The theft or vandalism of such historical markers is a kind of “stolen history,” and may signify social unrest. Over the summer in Greenville County, South Carolina, a sign indicating the site of the last person lynched in that state in 1947 went missing only two months after it was erected. It was found when turned in for scrap metal. In the days following Memorial Day of this year in Richland, Washington, four signs commemorating the war heroes for whom local streets were named disappeared. What could be a prank might also be a symptom of fraught times in small American communities.

Abbeville, a small community of 2,700, is located 100 miles southeast of Montgomery. As a heated center of the Civil Rights Movement, Abbeville is home to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a well-known hate crime watchdog organization. It was started by native Alabaman and civil rights lawyer Morris Dees, and currently monitors some 32 active hate groups within a 250 mile radius of Montgomery and Abbeville. Hence, the return and repair of such a historical landmark is important to this community which still routinely deals with a nervous legacy of civil tension.

A historical marker educates both travelers and residents of the great stories of the land they stand on. What battles were waged, what lives were lost, what poets commemorated – all are demarcations of our journey as Americans. When we view how Rosa Parks spent her childhood on the 260-acre farmland of her grandparents and went on to be the lynchpin of social change, we are seeing the sign of a time gone by and reminding ourselves of where we as a people have been.

A sign may be a simple gesture, ranging from $300 to $4,000 to erect, but the investment in a community’s history cannot be underestimated.

L. Dowda